by Willa Ross

Whatever its necessarily finished-unfinished form may mean in terms of the unrealized potential of The Other Side of the Wind, there’s not another 2018 movie I’ve spent so much time thinking about. Several months later, the layers of meta-meaning in Welles’s swan-song continue to play out across a long moebius strip in my mind, and each new circuit around the loop reveals something I’d missed on the last go-round (particularly after reading Josh Karp’s excellent making-of book Orson Welles’s Last Movie).

Those who were disappointed by Wind tend to turn their attention to the fact that Welles never finished it, and therein find evidence for how this created deficiencies in the film. I don’t agree with this perspective. It seems to me that the consensus — even among the film’s defenders — that a Welles-completed cut would have been ideal has shown an unhealthy level of certainty, and there is much to appreciate in its current (final?) form that would not be possible had the film been completed under his scissors and splices before his death in October 1985. The most moving example comes up front: instead of the room-filling thunder of Welles’s low, commanding narration filling the screening room over the opening montage of stills, we hear Peter Bogdanovich, in character as Brooks Otterlake. The text is near-identical to Welles’s, with the exception of a handful of new lines in which Otterlake, the hotshot acolyte of the fading genius of cinema Jake Hannaford, admits that it’s his fault the film you are about to see has taken decades to reach viewers “because, frankly, I didn’t like how I came off. But I’m old enough now not to care how my role in Jake’s life is interpreted.”

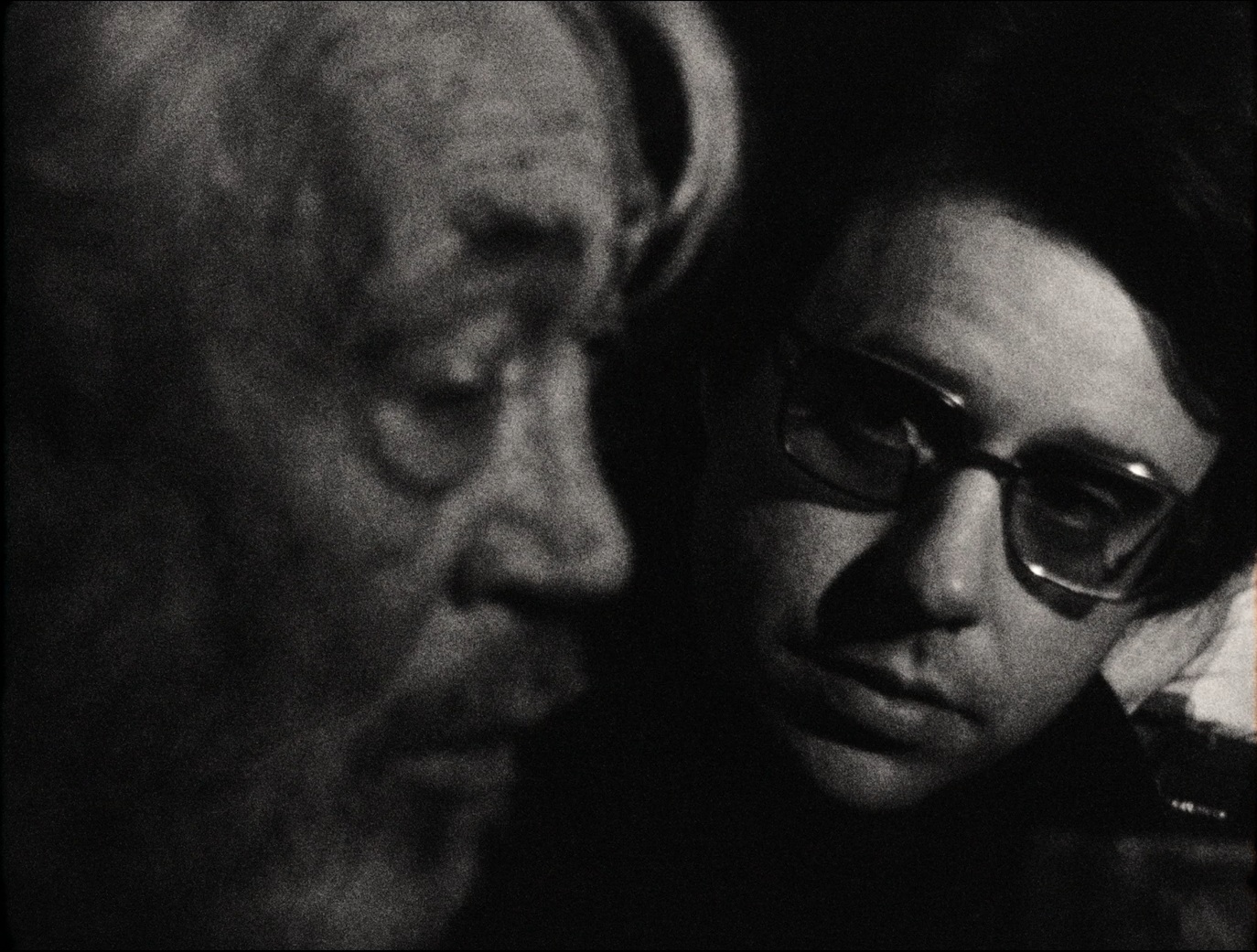

Otterlake, of course, is almost-but-not-quite a fictional mirror of Bogdanovich himself, just as Hannaford comes close enough to Welles that we can neither psychoanalyze the real man himself through the character nor dismiss him as being loosely inspired by the real legend’s personal fears and foibles. Bogdanovich’s own career trajectory, a comparable slew of disasters following an early breakout, makes the sound of Otterlake’s tired voice admitting defeat more poignant than Welles’s comparatively detached introduction could ever have been. It completes the cycle of the two men’s relationship; it connects the loop. The question of whether the two sides of that particular moebius strip are Otterlake and Hannaford or Welles and Bogdanovich is one of the film’s great gifts to its viewer, one that a 1985 Wind could not have offered.

Whatever my objections to the assumption that the best version of Wind would be one done in Welles’s lifetime, it’s certainly natural to consider this late-born bookend as an exercise in coulda-been. That open unfinishedness is a part of the movie’s DNA, a hodgepodge of sporadically-captured vignettes filmed in various formats that could only be assembled towards a clipped, elliptical result. The difference is that now the film is broadly seen as a finished-unfinished film, whereas the original effect would have been an unfinished-finished one. It's ironic that, besides a couple party scenes, almost none of the film-without-a-film — that is, the material about the fallen director Jake Hannaford on the last night of his life — was cut into any sort of "fine" form by Welles. However, excepting the nightclub sequence that sees Hannaford’s leading man silently pursuing his subject of sexual obsession into a bathroom, Welles finished editing all of the film-within-a-film himself. So the unfinished film that Hannaford so desperately seeks to find funding for is basically Welles's finished film, and the rest of the finished film we have now is Welles's unfinished film.

Puzzles and paradoxes like this are what make the metanarrative of Wind so rewarding. It’s no wonder why Netflix released a making-of documentary, They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead, alongside it. To appreciate what’s been accomplished here requires a viewer unafraid to search far outside the diegesis for answers. Wind almost seems to beckon the viewer to become an academically-minded scrutinizer of its own production, hunting through history for clues to the movie’s subtext. On one hand, that sounds like something Welles probably would have hated to do. On the other, the man seemed to enjoy playing tricks on himself as much as his audience.

But The Other Side of the Wind is an allegory for more than itself. The eventual relegation of Hannaford's Hollywood comeback film — an attempt to make something in tune with the current aesthetic trends — to a drive-in screening that nobody ultimately attends is itself a reference to Touch of Evil. Welles hoped that picture would announce his commercial viability in the States, following three prior projects without major studio backing. It was ultimately distributed as a B-movie and mostly seen, when it was seen, in drive-ins, and in a shape not at all commensurate with its director's final intentions. Thus we can read the film-within-a-film and its rejection by studio executives as not only a parody of Antonioni and a funhouse reflection of Welles's Wind itself, but also a bitter reflection on the last time Welles attempted to synchronize his artistic instincts with commercial practicality.

Welles insisted that none of this was autobiography. Yet these historical rhymes, along with countless other details of character, incident, and backstory, clearly confirm to all but the most credulous adherents of his denials that, more than anything, the man wrote and photographed a film that was (at least circuitously) about himself. Yet the famously imposing figure of Welles never appears. Instead of his intended role as the prologue’s narrator, he can only be heard in a few offhand lines as a journalist, a performance he almost certainly meant for somebody else to dub over later.

There’s more where that came from, more parallels between the actors and the characters they play, and the characters and other real people, and events and themes and truth and fiction. The film's extremely protracted production history may remove Welles's personal direction and inspiration from the Wind that’s finally available to us, but they also ennoble and enrich it as a work of aging and repetition and replication and generational inheritance and film history itself. This story at once takes place over the course of 12 or so hours and 48 years — the latter quality affirmed by the newly written allusion to cell phones in the prologue.

Jakes's bon mot of "it's alright to borrow from each other, what me must never do is borrow from ourselves" is, on the surface, an empty plaudit, designed to amuse an uncritical crowd. Still, it strikes at the psychological core of Wind's characters, who literally and figuratively project themselves onto and imitate and perform as other people, but refuse to display their inner selves. The collage-documentary aesthetic Welles chose works in counterpoint to this central theme: no matter how many angles, formats, stylistic departures, and movements you use to reveal the subject, the images will always be defined by what you don't see. This reminded me of Errol Morris’s Standard Operating Procedure, an actual documentary that insists on looking to the margins of documentation to find truth. Like so many Morris movies, SOP seems ahead of the curve for its time and place and has yet to see its more radical ideas picked up by others. The Other Side of the Wind, for its part, wrapped filming in 1976, was directed by the man who made Citizen Kane, and still saw no shortage of critical reactions that shrugged it off as being fairly unsubstantial. More than 30 years after his death and the canonization of several more of his movies, Orson Welles’s track record still can’t convince everyone to give the new stuff he tries a second thought.

Still, as painful as it is to convert that “tries” into “tried”, this pretty much wraps it up as far as new things for Welles to surprise us with (barring the discovery of his cut of The Magnificent Ambersons (or some kind of attempt to construct the Don Quixote footage into something Welles might have wanted. Who knows)). Thankfully, we’ve been left a more than worthy stylistic summation of Welles's career, and the techniques particular to him — deep-focus cinematography, lengthy, exploratory tracking shots, wide angle lenses, and, finally, near-cubist cutting patterns — are here used to photograph subjects who can never be truly known by anyone, even themselves, let alone a camera and editing bay. Like Rosebud, the tantalizingly incomplete and incoherent film-within-a-film-of-the-same-name promises a potential revelation of Hannaford's psyche that we can never truly access; likewise for Welles himself and his Wind, an approximated last testament for a man who, to the last, would disclaim that he was Jake Hannaford.

There is no Orson Welles to see here, said Orson Welles, a protestation he couldn’t have expected us to accept at face value. In the moment when the movie seems to suggest we can best "see" Jake Hannaford for who he really is — the devastating psychoanalysis by his nemesis film critic that he seems to affirm with his violent response — there is nothing to see of Jake but a disjunctive closeup that does little to place him in the space. At the moment of the slap and its aftermath, he's lost somewhere in a black void or beyond the frame, and he doesn't reappear until his final meeting with Dale back at the ranch. Maybe even more telling in this respect is the film's first visual, a photograph of the wrecked sports car that Hannaford used to end it all — a photograph in which he is nowhere to be seen. At his most exposed, Jake disappears from the picture. He vanishes into the same off-screen ether as his real-life author: the late, great Orson Welles, the most famous actor-director in the cinema's history, here remixing the meanings of that multi-hyphenation in a more original and difficult sense than anyone but him could have imagined.

![The.Other.Side.of.the.Wind.2018.REPACK.1080p.NF.WEB-DL.DD5.1.x264-NTG.mkv_snapshot_00.01.07_[2019.03.06_01.02.17].png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/578e7a0c197aea26a696f7f1/1551863475358-Z9FKC8J4QG939MQU2FO9/The.Other.Side.of.the.Wind.2018.REPACK.1080p.NF.WEB-DL.DD5.1.x264-NTG.mkv_snapshot_00.01.07_%5B2019.03.06_01.02.17%5D.png)